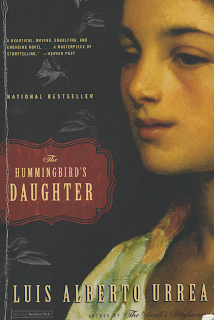

First impressions review: The Hummingbird’s Daughter, by Luis Alberto Urrea

I was intrigued by the premise of this book: A story about a young woman who was a sort of “Joan of Arc” to the Mexican revolution, extensively researched and written by one of her modern-day relatives. ‘The Hummingbird’s Daughter’ has a lot of the features I love in Latin American magical realism, including a big cast of varied and quirky characters and a mix of darkness, humor, and lushly sensual descriptions. I very much enjoyed it! However, if you are looking for a story about the Mexican revolution…this isn’t it! The conflict is barely starting in the last few chapters. The focus is instead on Teresa Urrea’s childhood and the world she grew up in and exploring what it might be like to become a “saint”, somewhat against your will!

Even if it doesn’t focus on the revolution, per se, the book does have opinions on what Mexico and The People are, which begin to be explained on page 8:

“On that long westward morning, all Mexicans still dreamed the same dream. They dreamed of being Mexican. There was no greater mystery. Only rich men, soldiers, and a few Indians had wandered far enough from home to learn the terrible truth: Mexico was too big. It had too many colors. It was noisier than anyone could have imagined, and the voice of the Atlantic was different from the voice of the Pacific…So what were they? Every Mexican was a diluted Indian, invaded by milk like the coffee in Cayetana’s cup…for all their beaver hats and their lace veils, the fine citizens of the great cities knew they had nothing that would ever match the ancient feathers of the quetzal.”

This focus on indigenous heritage continues throughout the book, both in Teresita’s insistence that she is Indian, despite her light-colored hair – rightly so, especially given how much of her medical and spiritual knowledge comes from that side of her heritage! - and in the focus on land-grabs from indigenous communities being one of the motivations for revolt. And not just that. Be warned: some of the descriptions of the things done (mostly) to indigenous people in this book are rather graphic!

The name of the book derives from Teresita’s mother, Cayetana, who is mostly known as La Semalú, the hummingbird. She doesn’t really know why she has this nickname, but hummingbirds are seen as god’s messengers by The People. Though this isn’t brought up in the novel, Aztecs also believed that warriors who died in battle would be reborn as hummingbirds – which seems oddly cutesy if you’ve never seen a hummingbird aerial dogfight! – and that may also fit with the themes of the story. Cayetana is fourteen when Teresita is born (yeah, more on that in a minute!) and eventually dumps her with her harsh-tempered sister, so Teresa’s primary maternal figure is Huila, the local curandera (medicine-woman). I love take-no-shit old ladies, so naturally Huila is one of my favorite characters! Take her interactions with Cayetana at Teresita’s birth:

“‘My sister,’ Cayetana gasped, ‘Calls me a puta [whore]’…’Hmm.’ Huila reached behind her and took a soggy mass of cool wet leaves and pressed it into Cayetana’s opening, ‘Too bad you aren’t. You’d have some money’… ‘Then I’m not a puta?’ ‘Do you believe you are a puta?’ ‘No.’ ‘Then you are not a puta. Push.’… ‘Huila – I have been bad.’ Huila snorted. ‘Who hasn’t?’ ‘The priest said I was a sinner.’ ‘So is he. Now rest.’ These girls, when the pain started, how they babbled!...Ay Dios. Huila was getting old and tired of it all.’”

I have some seriously mixed feelings about Teresa’s father, Tomás Urrea, who is the owner of the ranch. The story clearly wants you to like him, and there is a fair amount to like: He finds work for refugees who show up on his doorstep, makes a deal with the Indians who attacked one of his properties instead of slaughtering them all as some of his men wanted to do, is creative in uses of his land (getting really into beekeeping, supporting the building of a plaza to aid communal life), and develops a really nice, respectful, supportive relationship with Teresa. On the other hand, he did knock up a fourteen-year-old employee, and later pursues another woman who’s only 2 years older than his own teenage daughter! Eww. Granted, “age of consent” (beyond "have you had your period yet?") or employer-employee relationship power dynamics were not really a part of the discourse back then, but it was still theoretically considered bad to cheat on your wife by using the local peasantry as your harem…even if no one ever actually got in trouble over it! At least Tomás puts some effort into courting his girlfriends and making sure they enjoy their time with him, and acknowledges his bastard kids when he finds out about them. It was a bit mean of him to get mad at Buenaventura for ruining his marriage, when it was his own dumb idea to introduce the kid to his wife at the townhouse that is her haven. But the father-son relationship does recover, even if it is never as warm as his bond with Teresita – for whom he is willing to let thousands of dirty pilgrims camp on their doorstep, and eventually give up everything to take her somewhere safe from the Mexican government. Heck, their first interaction, before he knows he is her father, is already pretty cute: He finds this ragged, barefoot peasant girl listening to his grandfather clock, and his response to her statement that she’s been talking to this tree with a heart is to show her his pocketwatch (which she declares to be the “grandson watch”) and tell the kitchen staff to give her some cookies and juice. It would be cuter if I hadn’t been worried about the incest potential, given his record, though! Thankfully, that is never actually an issue.

Another important character is Lauro Aguirre, an engineer friend of Tomás who teaches Teresa to read and eventually has to flee the country when his revolutionary sentiments become known. This association also leads to the whole Urrea ranch having to pick up and move from Sinaloa to Sonora, which entails not only a lot of the expected travel-related troubles but also some culture shock: “Some of the locals had provided weird huge flour tortillas, and the men at the main-house ruins suspiciously wrapped their beans in these wads of what seemed to them to be wet laundry… Tomás chose to remain loyal to his little corn tortillas. There was only so much he was willing to concede to el norte.”

Teresita later gets back in touch with Aguirre, who has started a radical newspaper in Arizona.

The author’s note states that Teresa’s sermons and certain discussions are based on the notes made by Lauro Aguirre, her miracles on witness claims made at the time, and the teachings of Huila on notes from living curanderas from the region. The details of the attack by one of the farmhands that preceded her “death and resurrection” are kept vague because not that much is known about it – presumably including whether it included an attempted (or successful?) sexual assault, as is implied but not outright stated in the novel. I liked Teresita’s ambivalence about her new “saintly” role, and her practicality. For example, she would only heal for a certain number of hours so as not to totally collapse and be unable to help anyone. It reminded me a bit of her namesake, Teresa of Avila, who used to say that if you think you’re having a vision…you might just have fasted too much, so have a snack and see if it goes away or not!

Overall recommendation: If you are fond of Latin American literature and/or magical realism, or historical fiction, I highly recommend checking this out.