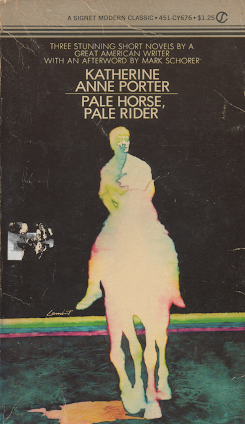

First impressions review: Pale Horse, Pale Rider, by Katherine Anne Porter

This short volume is really a set of three short stories. “Short novels,” the author calls them…and I can kind of see why. They pack a lot of feeling, character development, and setting into a very short page count. Porter is excellent at evoking a particular time and place. I’m not sure if this quite counts as historical fiction, as the stories are set between the late 1885 and 1918, and were published in 1936 (so the author’s life overlaps with some of it), but there is a sepia-toned quality to them.

In 'Old Mortality', two sisters from a well-to-do Texas family ponder the odd qualities of memory and nostalgia. They enjoy, for instance, the romantic stories of their beautiful Aunt Amy, who died tragically young, but they can’t see that romance in the stiff photo that remains of her, or the mothballed dresses and locks of hair their grandmother weeps over. And they are especially disillusioned to discover her dashing young suitor is an old drunk who has made his wife hate him with his constant betting on the horses and not being able to shut up about Amy. I found the shadowy figure of Amy kind of fascinating myself. She was clearly rebelling against the expectations of a Southern Belle, but it was in fits and starts, as she didn’t seem to know what it was she did want…and her death is rather suspicious. I also wouldn’t have minded finding out more about Cousin Eva the suffragette, though she too is an old woman lost in memories when we meet her. One sister, Miranda encounters her on a train:

“I think it was brave of you, and I’m glad you did it, too. I loved your courage.” “It wasn’t just showing off, mind you,” said Cousin Eva, rejecting praise, fretfully. “Any fool can be brave. We were working for something we knew was right…I didn’t expect to go to jail, but I went three times…We aren’t voting yet…but we will be.” Miranda did not venture any answer, but she felt that indeed women would be voting soon if nothing fatal happened to Cousin Eva. There was something in her manner which said such things could be left safely to her.

Miranda’s conclusion is that she’s going to leave the old people to their stories and live her own life truthfully. But can she, or do we all tell stories about ourselves?

'Noon Wine' follows a Texas farmer, Mr. Thompson. He is not initially a very likeable man, being both lazy and proud, a bit too keen on corporal punishment for his boys than either the modern reader or his wife would approve, and a bit too happy to pay the new farmhand, Mr. Helton, as little as he’ll accept. He also has weird ideas about masculinity and cares far too much about how the world sees him in general:

Mr. Thompson had never been able to outgrow his deep conviction that running a dairy and chasing after chickens was woman’s work…from the first the cows worried him, coming up regularly twice a day to be milked, standing there reproaching him with their smug female faces…All his carefully limited fields of activity were related somehow to Mr. Thompson’s feeling for the appearance of things… ‘It don’t look right,’ was his final reason for not doing anything he did not wish to do.

But Mr. Helton doesn’t care about that, and soon the taciturn, hard-working Swede has the farm actually making a profit. Mr. Thompson comes to value him, even if he is a little odd. When an unpleasant man shows up with the intent of making trouble for Mr. Helton, dredging up his past mental illness, Mr. Thompson defends him. While that can’t help but make the reader warm to him, there are violent consequences and public opinion eats away at Mr. Thompson. This is a Greek Tragedy of sorts, and his fatal flaw is that concern for how things look.

In 'Pale Horse, Pale Rider' we return to Miranda, who is now a single girl in the city, making her living reporting on the theater scene. It is WWI, and she and her other female colleague are being pressured by some rather unpleasant fellows to buy war bonds at $5/week, even though they only make $18. There is much allusion to the way people know they are supposed to talk about the war. Miranda has a boyfriend named Adam, but she can hardly bear to think of him like that, because he is to be a sapper1 and thus a dead man walking. But it is Miranda who begins to feel ill, and a reader who knows anything of history will immediately suspect that she has the 1918 flu. Adam nurses her very sweetly for a while, while they wait for the overtaxed ambulance service to come.

“Adam,” she said out of the heavy soft darkness that drew her down, down, “I love you, and I was hoping you would say that to me too.” He lay down beside her with his arm under her shoulder, and pressed his smooth face against hers… “Can you hear what I am saying? What do you think I have been trying to tell you all this time?”

She falls into a vividly described delirium:

Granite walls, whirlpools, stars, are things. None of them is death, nor the image of it. Death is death, said Miranda, and for the dead it has no attributes. Silenced, she sank easily through deeps under deeps of darkness until she lay like a stone at the farthest bottom of life, knowing herself to be blind, deaf, speechless, no longer aware of the members of her own body…yet alive with a peculiar lucidity and coherence.

I won’t spoil the ending, but at this point in the collection you will definitely be expecting something bittersweet, and you would not be wrong.

1. The kind of military engineer who does things like demolitions and clearing minefields.

Overall recommendation: If you like period pieces that don’t necessarily have a lot of action or plot but DO have a lot of character and vivid emotion (particularly melancholy), this would be the book for you!