The good, the bad, and the iffy in LGBT+ depictions (of my 2020 reading list)

When revisiting the books I blogged about last year I realized that half have some level of queerness1 in them. Some, such as ‘The Pull of the Stars,’ had representation that surprised and delighted me (the blurb not having mentioned anything about it), some…were a bit iffy. So I wanted to share my recommendations and reflect a bit on what worked well and what didn’t.

1. I’m going to be using “queer” and its variants a lot here. I know reclaimed slurs aren’t everyone’s cup of tea. If you prefer, you can skim the titles or click to the individual reviews where I often use more specific terms. Personally, I like having a one-syllable option that covers everything (acronyms with 5 or more syllables being a bit unwieldy). But I’m also the sort to take “weird” or “eccentric” as a compliment, so…

I’ve divided the books into those that definitely include LGBT+ characters, even if the precise label they should be given is unclear (canonical depictions, 13 stories/books) and those that have a ton of sub-text but nothing clearly confirmed (ambiguous depictions, 3 books). Within each category, the depictions are ranked from best to worst. Things that tend to place a depiction higher on the list is putting the queer characters in a setting where their queerness is totally normal/accepted OR the depictions of the challenges they would face is historically accurate (as opposed to worse than it should be); the queer characters having at least one person who loves and supports them; believable depiction of how the queer character would think about themselves given the setting; and good function of the character’s queerness within the story (eg. no tokenism, they aren’t treated as more expendable, etc.). Though I admit that if I just really love a particular character they will probably slide up the list a bit!

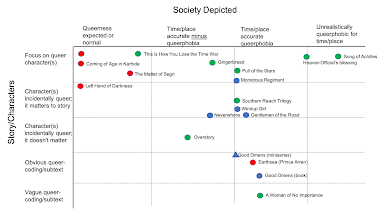

The good news is that almost all of these stories do at least some things right! I had thought about using a version of the ‘Invisible-Incidental-Focal’ and ‘Condemnation-Assimilation-Liberation’ axes used in Rowan Ellis’ discussion of queer representation in movies, but quickly realized that wasn’t going to reflect the main differences here. For one thing, none of the characters were ‘condemned’ by the narrative (yay!). For another, the way the societies of the story were depicted ended up mattering just as much for whether it felt like good representation as how the characters themselves were written. A thumbnail version of the graph I came up with is shown above; A bigger version with explanation is posted and explained below the list (or you can just jump right to that overall analysis if you prefer).

Canonical depictions

1. ‘Unchosen Love’ (1994), ‘Mountain Ways’ (1996), and ‘The Matter of Segri’ (1994)

In these Ursula LeGuin short stories, bisexuality isn’t just common or accepted, it is considered standard – which, combined with other aspects of the culture, affects what conflicts characters face in their romantic relationships and how life in general works for them. That approach is still quite unusual (see my rant about ‘The Song of Achilles’ below)…but these stories were published 30 years ago! So major props to LeGuin for that. Also, these stories should be a textbook example of how to create vivid characters and worlds with a minimal word count; it is honestly astounding.

Content: The first two are basically love stories, and pretty “safe”. ‘The Matter of Segri’ explores the light and dark sides of the society it depicts, with the latter showing up in accounts of psychological and physical abuse, rape, the murder of a gay character, and the resulting violent revolt. None of this is gratuitous – it all works toward the point of the story - but bear it in mind when deciding when to read this.

2. ‘This is How You Lose the Time War’ (2019)

The main characters of this book, Red and Blue, undoubtedly have a different concept of gender than we do currently, coming from societies where people are grown and everyone is ‘she’. The conflict in their relationship comes not from the fact that they both consider themselves women, but rather that they are time-traveling agents on opposite sides of a war meant to ensure that either Red’s Matrix-like Technotopia or Blue’s organic hive-mind Garden is the true future. But they start exchanging messages – sometimes letters as we know them, sometimes messages in tree rings or tea – and fall in love. Red admits: “To be honest, love confuses me…I’ve had joy in sex; I’ve had fast friendships. Neither feels right for this, and this feels bigger than both…when I think of you, I want to be alone together. I want to strive against and for…I love you, and I want to find out what that means together.” Gaahh! This book – their banter and their striving to find a third way, and the words in which it is described – is so gorgeous. And, like the previous entry, there is an incredible amount of story and world-building in under 200 pages.

Content warning for (mostly kind of stylized) violence and an apparent suicide (but bear in mind that in some threads ‘Romeo and Juliet’ is a comedy, not a tragedy).

The main character of this magical realism-style novel is a black bisexual woman who is does not seem to experience any discrimination or angst due to either point. This is a little odd considering that even if she grew up in a country that lacks “distracting inequalities, stuff about physical appearance and who people should and should not fancy, and places of prayer that were better than others”, she now lives in our world. But I will happily roll with it. In a story where dolls talk, you don’t have to make the social conditions 100% realistic unless that is the point, and the author clearly wants to focus on economic exploitation2. There are also two subversions of romance story tropes that I didn’t want to spoil in my review, but I love them and really wanted to talk about them, and they involve other queer characters (yes, Harriet isn’t the only one in her social circle!) - so click here to read about that.

2. This theme gets rather suddenly dropped near the end, but there is some good sharp commentary in the earlier parts.

4. ‘The Pull of the Stars’ (2020)

This historical fiction follows three days in the lives of three women working in a Dublin maternity ward during the 1918 flu; Early hints that none of them are straight soon get confirmed. The POV character learns a lot through her conversations with the others, their struggles to keep their highly vulnerable patients and their babies alive makes for a highly gripping read, and the romance that starts to bloom between two of them is beautiful in a bittersweet way. The author’s note reveals that the third character is actually a real lesbian (socialist suffragette Irish revolutionary) doctor who got a happier ending than any of the fictional characters in this book, which was a nice upbeat "chaser" and made me want to read her biography.

Content warning for death, stories of child abuse and neglect, and the kind of blood and body horror that comes with childbirth and the 1918 flu.

5. ‘The Left Hand of Darkness’ (1969) and ‘Coming of Age in Karhide’ (1995)

In ‘The Left Hand of Darkness’ LeGuin conducts a thought experiment – what if there were a human society without any permanent sex or gender? How would that affect the way civilization and culture develops, and the way people live? The Gethenians are "ambisexual" – asexual and androgenous except when they periodically enter a sexual state called kemmer in which they may be either male or female. The book POV switches back and forth between an earthling visitor named Genly Ai - who has a bit of trouble adjusting to this world (especially since he distrusts what he perceives as feminine) – and Gethenian Estraven who is on a personal mission to help Genly convince his people to join the union of worlds called the Ekumen. I say "his" because the book uses male pronouns as the default; LeGuin did this because using "they" to signify a person who is neither male nor female wasn’t really in the discourse in 1969. But she wasn’t happy about how this turned out, since it led a lot of readers to think of all the Gethenian characters as men rather than both/neither. She was able to address that – and the question about whether, when in kemmer, Gethenians always pair up as male-female – with the short story ‘Coming of Age in Karhide’. The last line kind of says it all: The old days or the new times, somer or kemmer, love is love.

Content warning for death and gulag-type mistreatment of

main characters in 'LHOD'. The short story is pretty sweet (though way more sexual, since a good chunk of it takes place in the kemmerhouse).

6. ‘Monstrous Regiment’ (2003)

I was nervous to re-read this, the only Discworld novel to put issues of structural sexism, gender identity, and (to a lesser extent) sexual orientation front and center, with 2020 eyes, but I actually think it holds up fairly well. As I cover in my review, some parts are awkward to read if you are sensitive to potential misgendering…but the way characters are thinking and talking about these issues feels accurate to the culture they come from, or even slightly more progressive than you’d expect. I go into detail in the spoilers section of the review but I think there are two things I can say without giving too much away. First, there is a pair of characters who are (with 99% certainty) a lesbian couple and that is not questioned at all by their friends. Of course, the whole group would be “abominations” of one sort or another in the eyes of their culture(s); they seem perceptive enough to realize that3! Second, while a book written now (perhaps even by this author if still alive) would hopefully handle the gender identity issues more smoothly, the treatment of the character that most clearly reads as trans is good. The POV character learns his backstory but his deadname is never revealed and it is clear that he has no interest in living as a woman. She then suggests a way he could reunite with the son he gave birth to without outing himself, and goes back to calling him ‘he’.

I’m not qualified to say how this story would read to an actual trans person today; I think it may stray a bit too close to treating gender identity as a choice. But I’m inclined to be happy that, nearly 20 years ago, Pratchett got as much right as he did in his effort to include a sensitive and positive portrayal of non-cis/het characters in his popular-with-all-ages fantasy series. Yes, that is a jab at JK Rowling. Pratchett was born in 1948, making him almost a full generation older than Rowling – and he had already metaphorically nodded to these issues in prior Discworld books, notably by including a werewolf character who has dated both wolves and humans (and also gets hostility from both species) and by having an ongoing storyline about dwarf society grappling with some of its members wanting to wearskirts or lipstick and be called ‘she’ (the more conservative dwarves showing a tendency to spit that particular pronoun). Not to mention the central relationship in 1990’s ‘Good Omens’, which we’ll get to below.

3. Which is more than you can say for some in our world, unfortunately.

7. ‘Heaven Official’s Blessing’

This Chinese web novel (translation linked in the review) follows the adventures of, and relationship between, repeatedly demoted but genuinely good-hearted heavenly official Xie Lian and dramatic, sardonic demon/ghost king Hua Cheng. The episodes range from hilarious rom-com-style shenanigans to super dark and angsty, and the world is very clearly established so that even readers who have no familiarity with Daoism or Chinese folklore should be able to follow (eg. how Xie Lian as a human prince gets promoted to deity and why he loses that position the first time). That’s not to say there aren’t some issues. Hua Cheng is arguably a bit stalkerish…but since obsession is an essential component to being a ghost, and Xie Lian is the kind of person you could picture someone having a “dammit, I can’t die; I have to stick around and protect this adorable creampuff4” reaction to, it kinda works. The other heavenly characters are probably a bit too homophobic for Ancient China5. However, you could interpret much of their alarm/disgust/shock as being about Xie Lian dating a demon, which would be a more reasonable concern. Finally, among the various annoying author notes is one that is essentially “there aren’t any other gay characters in this story, so don’t go shipping these two with anyone else”. That’s highly unnecessary, especially considering that a nice way to balance out the haters would be to include some lesbian goddesses who quietly give them a thumbs up! But even so, these Xie Lian and Hua Cheng have such a fun dynamic and the ending is so lovely and heartwarming that I’m willing to forgive those flaws. Oh, and there’s also two characters that change gender from chapter to chapter. They have this ability because their worshippers got confused about what gender they originally were - That’s kind of a cool extension of the influence that belief has on deities’ powers in in general.

Content warning for occasional graphic violence and body horror, mainly in the “flashback” chapters.

4. Not that Xie Lian is always nice – there is a character that is specifically trying to corrupt him, which wouldn’t be compelling if there weren’t any dark impulses to work with. Nor is he helpless; He is a martial god and a huge sword geek. But his powers are weakened for most of the main part of the story, and he has something of a habit of trying to do good and getting himself into trouble in the process…giving Hua Cheng lots of opportunity to play knight in shining armor (even when Xie Lian doesn’t realize it).

5. That mostly not being a huge issue before the 18th or 19th century and growing European influence, though there was fluctuation from dynasty to dynasty.

8. ‘The Southern Reach Trilogy’ (2014)

As noted in my review, this series gives both nods and middle fingers to HP Lovecraft. Most notably, all the characters who survive the mysterious Area X long enough to be main characters belong to at least one marginalized group, and sometimes several. This actually makes total sense: “Oh, you say there’s a weird force that wants to kill or assimilate me? You know that’s basically a Tuesday for me, right?” There’s at least two confirmed queer characters among these. One is the lighthouse keeper, a gay former preacher who moved out to this stretch of coast to live a more authentic life. The other is the assistant director of the Southern Reach, a black lesbian woman whose devotion to the original director long after her disappearance into Area X (a major factor in the conflicts of book 2) suggest that more than collegial feelings may be at play.

Content warning for death and body-horror.

9. ‘Gentlemen of the Road’ (2007)

I wasn’t sure where to put this book on this list, as the representation is a tad ambiguous. But I really love the characters in this book, and Zelikman - half of the central pair of traveling mercenaries/swindlers/thieves - is basically outright stated to be asexual. So #9 it is. As I cover in my review, there is another character who might by modern definitions be considered a trans man, non binary, or gender fluid but it isn’t 100% clear because (much as in ‘Monstrous Regiment’) the characters don’t have any of those concepts in their 10th century vocabulary. Both are well written, sympathetic characters who not only like and support each other but seem to be accepted by their companions, notably Zelikman’s partner in crime Amram. However, as covered in my review, there are two choices made involving these characters that, while not technically unrealistic, are not necessary to the story and which I would edit out if adapting it.

Content warning: Violence, allusions to anti-Semitism, off-screen rape, and possible misgendering (depending on how you interpret character’s gender)

The Environmental Ministry “white shirt” Kanya is a sort of “secret protagonist’”in this book – that is, her decisions have a much bigger influence on the plot than is immediately obvious – and a good example of incidental queer representation. The fact that she sometimes or always dates women comes up twice. First, it is mentioned by the wife of her boss Jaidee, and the tone of the conversation indicates that they don’t judge her for it and care about her happiness6. This is refreshing in a story featuring a lot of prejudices, and Kanya’s relationship with Jaidee is very plot-relevant. Second, Kanya goes to see said ex-girlfriend, a scientist, later in the book. Their interaction indicates the breakup was amicable - a point in grim-faced Kanya’s favor - and the conversation conveys important plot information.

However, I’ve had a few thoughts about the “lady boys” since I wrote my review. While you get the impression that these individuals are an accepted part of post-apocalypse-future-Thailand, they don’t seem to have a particularly high status. At least not the ones we get to see, who were given to a morally deplorable and physically gross but extremely useful foreign scientist as part of his government payment. There was an opportunity to reveal how they feel about this – as we had for the titular ‘windup girl’ Emiko, a genetically modified human – in the form of Kip, who shows up in multiple scenes. But Kip remains outwardly serene and unbothered. Of course, Kip and “Gi Bu Sen” do meet up with a liberated Emiko at the end. That could lead to some really interesting conversations and dilemmas, with Emiko perhaps being torn between wanting the skills Gibson offers to make her own people more independent and seeing her former subservient and exploited self in Kip. But I don’t know if a sequel ever explored that.

Content warning for graphic violence (some sexual in nature), as well as racism/ethnicity-based bigotry…though not involving the characters in question (at least on page).

6. Well, the wife does talk about finding Kanya a nice boy. It could be considered a “just a phase” thing…but since she does seem to regret that it didn’t work out with the girlfriend, I prefer to interpret it as her knowing or guessing that Kanya is bi.

Hunter, hired by the main characters to guard them in their travels through London Below, has a distinct ‘Xena, warrior princess’ vibe. She does indeed turn out to be into women and this has some minor plot relevance when some kind of prior relationship with Serpentine leads to this otherwise fearsome character giving the group shelter. That’s about it for representation in this book – which could have done a bit better given how many of the people who “fall through the cracks” and thereby end up in London Below would be, say, homeless queer teenagers. But I like Hunter, who not only kicks ass and looks good doing it but is a morally ambiguous character with her own driving motivations.

Content warning for violence.

12. ‘The Song of Achilles’ (2012)

You might be surprised to find this book so low on the list given how much people usually seem to rave about this re-telling of ‘the Iliad’ as tragic gay romance. True, the writing is beautiful and the relationship between Achilles and Patroclus is sweet and heartbreaking…but the way other characters respond to them is extremely weird for the setting. I go into this in way more detail in my original review, but basically: It should not be possible to write what feels like a “bury your gays” story set in Ancient Greece because bisexuality/pansexuality for men was the default assumption.

Having no other male-male relationships and having other characters side-eye the main pair, I would argue, unintentionally reinforces modern homophobia by acting like it has been a constant across societies. I wish Miller had pulled a page from Ursula LeGuin’s book and explored how real Ancient Greek assumptions about how love and relationships work would have presented challenges. For instance, Achilles and Patroclus seem to have a pretty balanced and reciprocal partnership and that is what would have raised eyebrows at the time – what mattered was not gender but role, and the expected roles were unequal7. Such an approach would have been more challenging to reader’s assumptions as well…but that, of course, might have meant less mainstream popularity!

Content warning for lots of references to sexual abuse of women and one incident of sexual coercion directed at Achilles. Also war-related violence, but not in the brutally realistic way.

7. Miller studied Classics; she can’t be unaware that most arguments in antiquity from Athens to Rome were not about whether Achilles and Patroclus were a couple but about who was the ‘lover’ and who the ‘beloved’.

This book has what I’ve been thinking of as an “un-fired Chekov’s bisexual”. The author keeps bringing up the fact that Mimi Ma sometimes dates women but, unlike with Kanya in ‘The Windup Girl’, we never meet any of them and Mimi’s sexuality does not seem to affect her life or political views in any way, unlike her status as an immigrant’s daughter…which is weird given that the story is set mainly in in the ‘80s and ‘90s. Ah, but it does make her extra exotic and interesting to a man. Sigh. Seriously, the book was great when talking about trees, but between this and some of the characterization of women in general, I cannot believe this story was written in this decade.

Content warning for violence toward peaceful protesters, and a few major character deaths (including at least one suicide).

Ambiguous representation:

This book has long been a favorite, and I was delighted by the 2019 mini-series adaptation including the way it was clearly (though still technically sub-textually) indicated that the demon Crowley and the angel Aziraphale had romantic feelings for one another. Then it hit the final scene, where they are dining at the Ritz and ‘A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square’ plays, and my brain I exploded. “WAIT. That’s what the nightingale thing in the book was about? Their last scene references a 1940s love song? How much of this was already in there? I must re-read it immediately!” Long story short (you can see the full point by point analysis at the end of that review), this book is now my yardstick for queer coding. One GO unit means “You could miss it8, but once you see it…”, 0.5 GO means “You can read it that way, but it is probably not intentional”, and 2 GO units means “Seriously, there is no straight explanation for this.” Although there probably is no straight explanation for Good Omens. Neither “man-shaped being” has eyes for anyone else, even if sex isn't something angels/demons do…which may be why this book seems to have a fairly sizeable asexual fan base.

So how is the representation, viewed through that lens? Well, Aziraphale and Crowley are terrific as characters. They are both really likeable and distinct and have great banter. They have better chemistry than either of the main male-female pairings in the book. Interestingly, Sergeant Shadwell and Madame Tracy technically get no more textual confirmation than Aziraphale and Crowley, but no one questions that they are together by the end! In the book, Aziraphale is regularly presumed by humans to be “gayer than a tree full of monkeys on nitrous oxide”. This has surely been a nuisance – heck, in a line very wisely cut from the adaptation, he gets the f-slur thrown at him by an eleven year old! However, given his powers, bigotry has unlikely been a physical danger, which may be why he can so confidently own another insult: “Not just A southern pansy, Sergeant Shadwell, THE southern pansy!” Crowley has more subtle coding, but he is the one who pushes to stop Armageddon, the one who rushes into a burning building to try to rescue his partner. Which is perfect, since caring about someone else is what would be dangerously deviant for a demon! The main barrier to any sort of relationship is being on opposite sides of heaven and hell’s long cold war - not that that stops them from hanging out and eating crepes in the middle of the Reign of Terror and such. Anyway, I guess my conclusion is…you can only get so far with subtext, but here it is fun, has a happy ending, and led to a modern version where they get to be more openly flirty. So I won’t complain!

8. Especially if you first read it as a dumb teenager who didn't know anything about Freddy Mercury’s personal life, say.

2. ‘A Woman of No Importance’ (2019)

This is the true story of Virginia Hall, a one-legged American spy who ran some massive operations in support of the French Resistance right under the nose of the Gestapo for a total of 3 years during WWII without getting caught. Not only did she escape capture herself, but she managed to spring dozens of her less careful or less fortunate colleagues out of custody. That is an amazing story already. I was excitedly live-texting it to two of my friends and halfway in was like: “Hey. You know I don’t like assuming every pre-1980s career woman was a lesbian. But…I feel like I’m getting some serious Sapphic vibes from this one.” And my (straight) friend texted back with a point I hadn’t even considered yet! What I had noticed was passages like this: "Virginia held such displays of male ardor in contempt...and would assert her independence by wearing tomboy trousers and checked shirts whenever she could." Not to mention name-dropping Josephine Baker and Gertrude Stein among the luminaries young Virginia might have encountered during her early time in Paris! Multiple members of her most loyal inner spy circle also get statements made about them that, in a fictional narrative, I would definitely call queer coding. And yet, at the same time, the author will do things like say one of the things that upset Virginia about losing her leg was potentially never getting a husband. “What? You’ve been painting her as actively avoiding marriage for several chapters now. I am seriously confused.” Then, trying to google information about the book, I was reminded that the title comes from an Oscar Wilde play. So…I’m not sure if it is wishful thinking that makes me want to turn this into “gay Inglorious Basterds” or if the author is just being way more coy than should be necessary in 2019. We likely wouldn’t get a full answer even if we could ask Ms. Hall, since being not-straight was considered a security risk back then and she was very good at covert operations!

3. ‘Earthsea’ series (1972-2001)

Even as a fairly clueless 14-year-old, I read ‘The Farthest Shore’ and thought: “Huh. Prince Arren really seems like he has a crush on [main wizard character] Ged.” When you sit down and read the last three books in the ‘Earthsea’ series back-to-back that impression only strengthens… which makes the ending for Arren (or King Lebannen, as he’s known by then) rather odd. As I outline in the essay linked above, it isn’t so much that he seems to have pined over Ged for a decade and a half and then marries the princess Sesarakh – no reason he can’t do both, after all! But we don’t get to see him make the shift from the “confirmed bachelor” mindset to actually wanting to marry her, and that is concerning. In fact, the last thing we get from his perspective is remembering his travels with Ged while he watches dragons fly over what had been the land of the dead (the site of the climax of their adventure in book 3)...and he almost doesn't come back. Given Ursula LeGuin’s other work (see above) I can’t believe the subtext – if you can call it t that9 – was accidental. I’m not sure why she choked at the ending, giving such a hurried comp het conclusion. It makes me wonder if there was some kind of publisher interference involved; they certainly seemed to have an issue with making it clear on the covers that the characters aren’t white. Since all fantasy was for some decades marketed mostly to young people, and since even PG gayness is still widely considered not family-friendly, I certainly wouldn’t rule it out.

9. Arren’s feelings toward Ged are literally called “romantic” and thinks of the wizard as “the man he loved above all others”. He wears over his heart, always, a rock that fell into his pocket as he carried Ged over the mountains of Pain at the edge of the land of the dead. I mean…good lord.

The graph: Book List

OK, so these depictions can be sorted out along societal and character axes. The depictions of societies range from some that are more queerphobic than they should be for the time and place (bad); to those where the society is accurately depicted, including any queerphobia (not fun to read, but can be important); to those where most of the society is accurately depicted but queerphobia that would have been there is minimized or absent; to those where what we would call queerness is actually the societal norm (always really interesting and fun to see!). The character axis runs from queercoding/subtext, which can be vague or obvious (ie the author almost certainly intended it!); to cases where a character is “incidentally queer” and that either has no effect on the story (not ideal) or influences something (better); to stories that actually focus on those queer characters.

Looking at the resulting graph, a few things stand out. First, Ursula LeGuin (red dots) was way ahead of her time! Most of her stories end up in the top left, with queer characters who are central or important to the story but who live in societies where the features of their gender or sexuality that would make them “queer” in our society are actually totally normal and accepted – meaning we get to have a look at what such a society would be like, and what types of stories can be told when something else is the problem that has to be dealt with. She had a stumble with regard to Prince Arren, but otherwise stellar work! Of the works from other authors, published 1990-2009 (blue) are in the middle of the “society” axis, as if those authors were trying mostly to stick to reality, maybe leaving out some of the more unpleasant details. Finally, the works by other authors from the most recent decade (green) are all over the damn place!

It will be interesting to see if these patterns hold up in my readings for the next year! Got off to a bit of a disappointing start with ‘Lagoon’ (an excellent book in all other respects)…but we shall see.